Revolution of Art

The production team for this episode is:

Research and Interviews: Mai Abusalih, and Mohammed Awad Mustafa.

Presenter: Azza Mohamed and Zainab Gaafar.

Script: Mohammed Awad Mustafa, Dahlia Abdelilah and Husam Hilali. with assistance of Zainab Gaafar and Azza Mohamed

Music: Zain Records.

Audio Mixing: Tariq Suliman.

Project Manager: Zainab Gaafar.

Recording studio: Rift Digital Lab

Poster design: Azza Mohamed

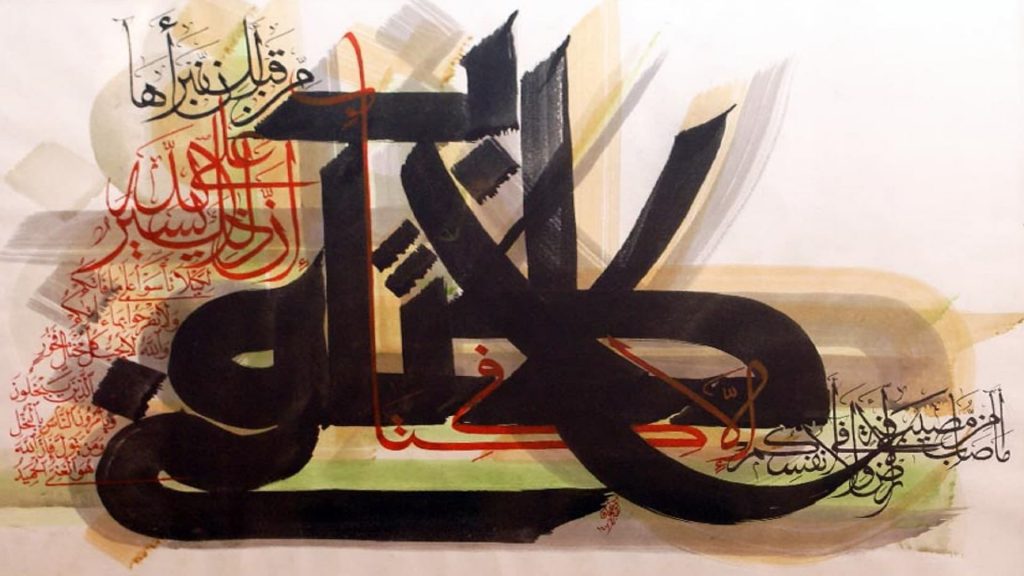

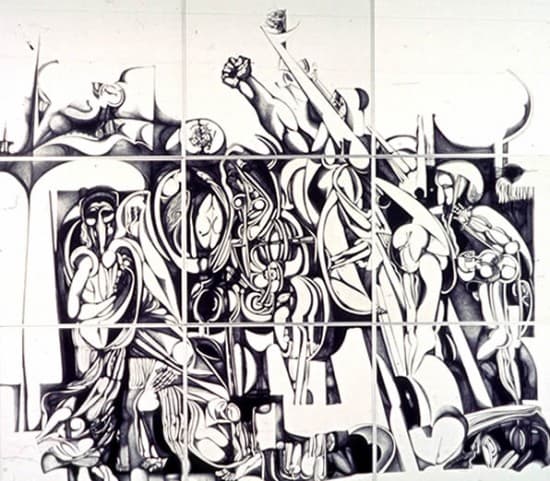

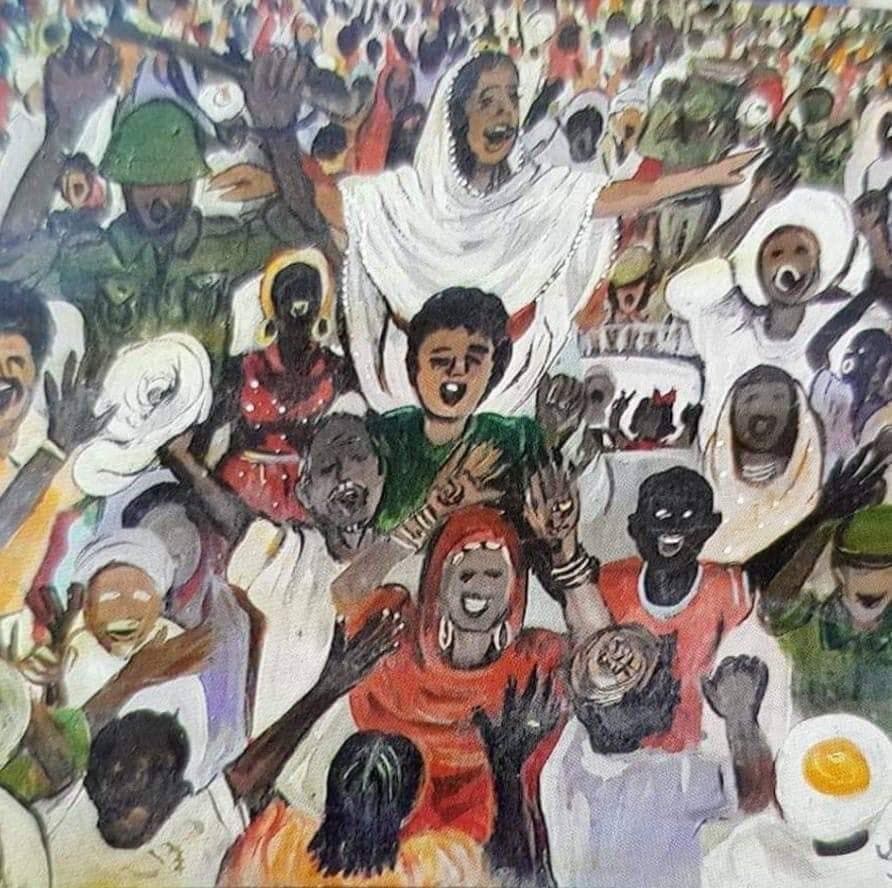

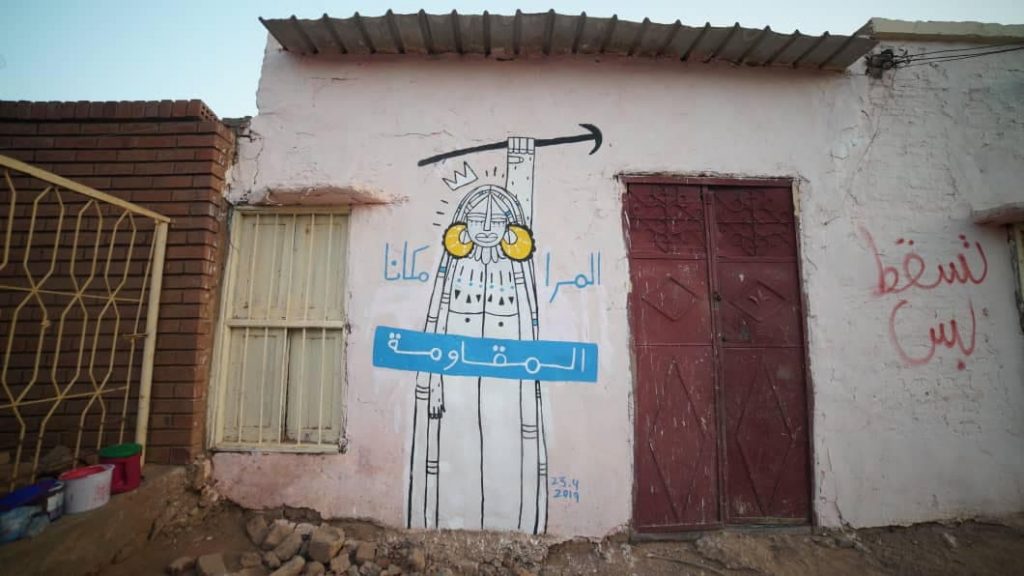

All artworks mentioned in the episode are below

Shaping a Sudanese Artistic Memory

Original essay by: Rund Alarabi

Translated By: Mais Abdullah Saleh Abdulrahman

This essay explores Sudanese artistic spaces in their various forms, and the rippling effect that they may have on our mental spaces. This is especially regarding the nature, type, and definition of the works of art. As such, this article will also discuss the absence of a permanent, comprehensive space for different kinds of Sudanese art and their impact on our local, collective memories. It is a spatial exploration of the literal and metaphorical role art plays in our past and present Sudan.

Memory as a Mobile Museum; Exploring Local and Artistic Memory:

The lack of archival records, photo documentation, and other accessible resources on the history of Sudanese art begets a situation where the names of many artists and figures are heard of, yet the artworks themselves are withdrawn from sight. The task of getting acquainted with the history of modern and contemporary Sudanese art usually depends almost entirely on one’s research effort. Reading up on texts and various opinions precedes viewing the artwork in real life. Despite the many factors contributing to the formation of this issue, it is necessary to shed light on one of the most significant consequences of the aforementioned lack of resources.

There is a radical impression caused by the existing gap between art making and seeing the artwork, and its impact on the quintessence of art and the extent it relates to the local community as a whole. A marked effect can be noted from the absence of an inclusive, permanent spatial and social relationship between the artist and a society that enables him to display his work and exchange criticism, thoughts, and opinions. This leads to the weakening of society’s connection with art as well as reducing the likelihood of its permeation into various aspects of daily life.

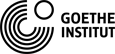

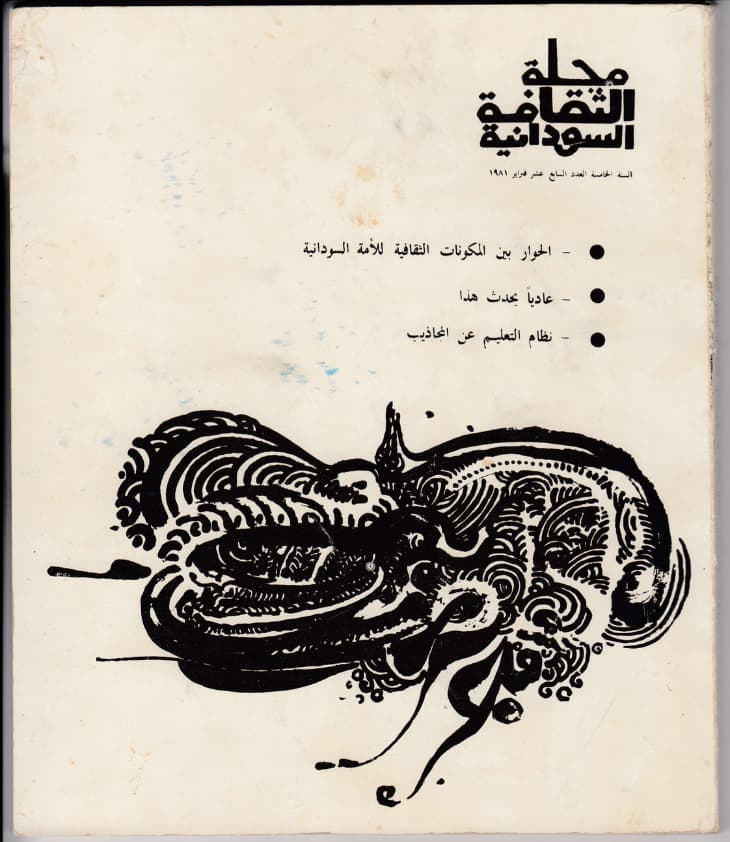

The literary sphere of the past was shaped by several writers and thinkers who influenced and were in return influenced by the scope of artistic discourse and criticism. Eventually, their musings and discussions would transition from the oral format to the written one when numerous publications and literary works emerged around the mid-20th century. Their subjects revolved around literary, cultural, and artistic critique, discourse on various topics, including interviews with artists to forge a connection between the readers and artists (Khartoum Magazine and Sudanese Culture Magazine being notable examples, among others). They promote the creation of a portable intellectual space capable of transcending spatial and temporal boundaries; thus, permeating the minds of many of their readers and serving as a documented record of these conversations. Later on, these voices would become muffled due to various regulatory, political, and economic reasons, resulting in the free editorial space gradually dwindling until it completely disappeared for some time.

In the last few decades, the art scene has witnessed several changes concerning the types of artistic disciplines and the concepts contained within the resulting artwork. This is especially seen with the emergence of digital databases, which in turn provided artists with access to vast amounts of open-sourced knowledge, launching a revolution that altered the artistic trajectory of many, while casting its shadow on the public’s views on art, its essence, and its importance. However, the right to practice art is still deemed by some to be dictated by either their belief that producing a work of art requires a spark of divine inspiration capable of invoking itself and is self-sufficient, inspiring the artist and imbuing him with intellectual and applicable capabilities, or by restricting the concept of artistic endeavor to an elitist framework, with a limited scope based on concepts detached from its original contexts.

When it comes to traditional and applied arts such as pottery, woodworking, and blacksmithing, the Sudanese contemporary art scene might be standing at a crossroads. On one hand, they can be categorized as an art form; or they can forgo a designated label entirely. The danger of these specified classifications is the possibility of obstructing and disrupting the innovative process and creation of new artistic ideas, expressions, and symbols that can transcend far beyond the well-known classifications and terminologies.

Political Negotiations in the Exhibition Space:

State politics have had a long history of interference with the Arts. Sometimes the State’s attitude was favorable; such as when arts are necessary for promoting its propaganda and curricula. Other times it enforces oppressive and obstructive tactics to suppress artistic endeavors, attempting to suppress public opinion and silence dissent.

The notion of art exhibition was once exploited by the colonial state as a tool for promoting state propaganda. Even post-independence, authorities continued to adopt this approach; political organizations like the Sudanese Communist Party, for example, would use art galleries as an introduction and motivator to encourage individuals to join their faction and take up political action.

During the more politically stable years (1969-85), President Nimeiri was able to establish cultural institutions, promoting the idea of art galleries as exceptional representational spaces. They were also tested out by political parties, like the Umma Party, which in turn used art galleries to reflect a modern and attractive image of their political project. Politically oriented art galleries can impact both political and artistic activities, which can influence more artists to impose more of their political leanings in their work to serve and survive the status quo, thus affecting their artistic vision and altering the trajectory of their practice.1

Despite the ever-rotating seats of power and the rise and fall of several regimes, political censorship and surveillance would continue to tighten their chokehold on artists, restricting their freedom of expression and preventing them from expressing their truest selves to the public. Intellectual censorship was a tactic inherited from colonial rule and was readily adopted by several governments post-independence, employing a totalitarian approach with varying degrees of control. This in turn helped isolate and stifle the artist’s ideas and thoughts which didn’t align with the State’s political and intellectual agendas.

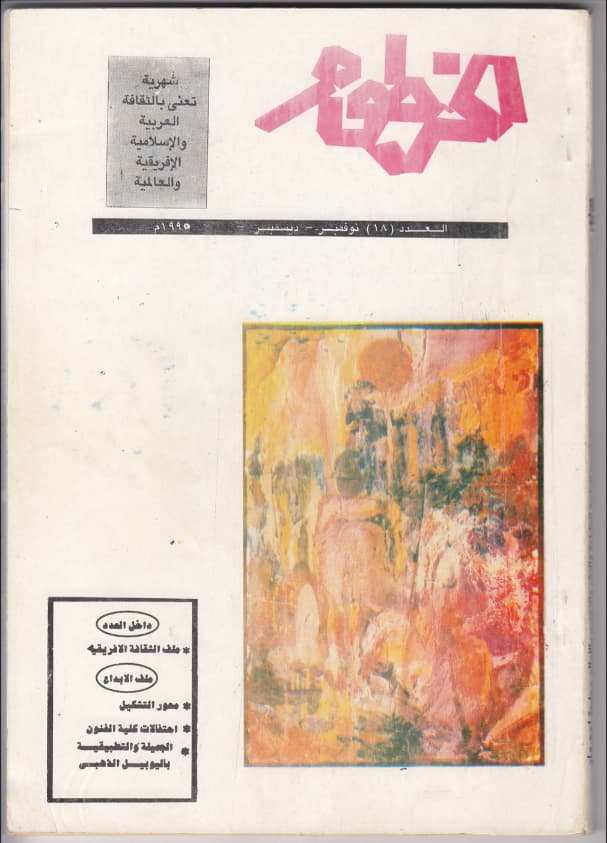

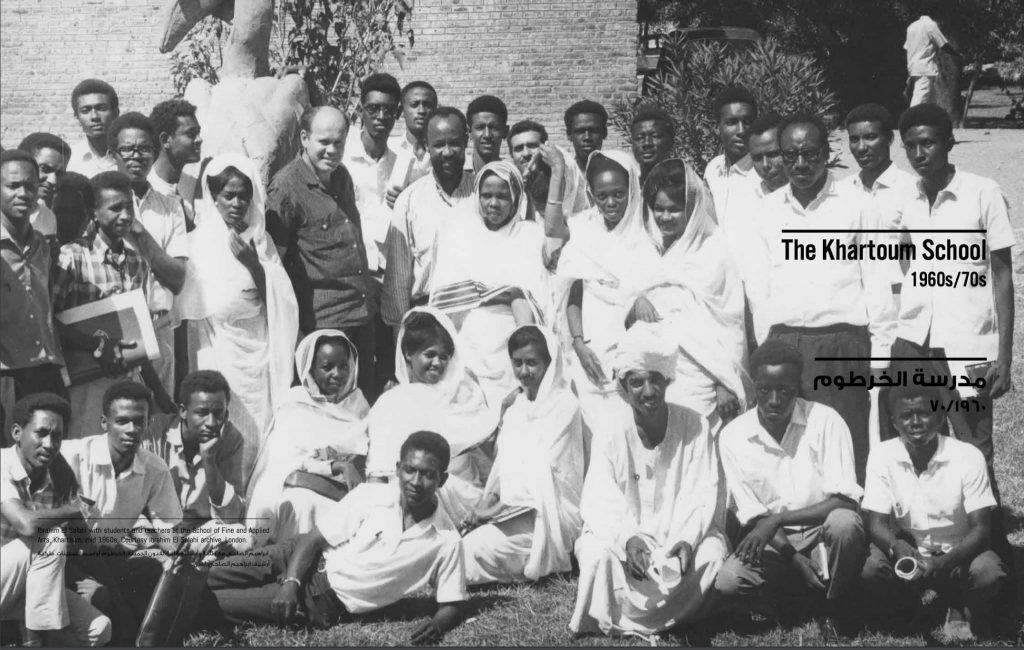

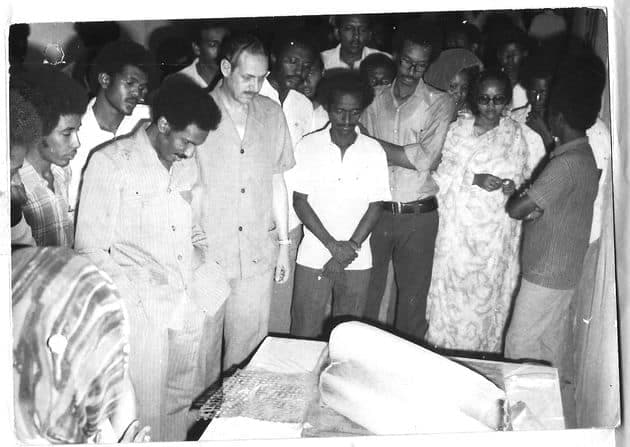

Even though there are numerous examples one could draw upon, the experiences of the artist Ibrahim Al- Salahi are incidents that we must address. Despite his contributions to founding a school of thought, working as a professor in the School of Fine and Applied Arts, and holding positions of authority, he was not safe from Jaa’far Al-Nimeiri’s political dungeons. Neither his positions at the Ministry of Culture nor the National Council for Culture and Arts was to pardon him or intercede on his behalf from the six months and two days imprisonment he spent in Kobar prison. In addition to the house arrest, he was placed under, following his release from prison, due to false accusations of his involvement in plotting a coup against the regime in 1975 AD. These experiences affected his artistic style and altered his career path, and were ultimately a key factor in his decision to emigrate.2

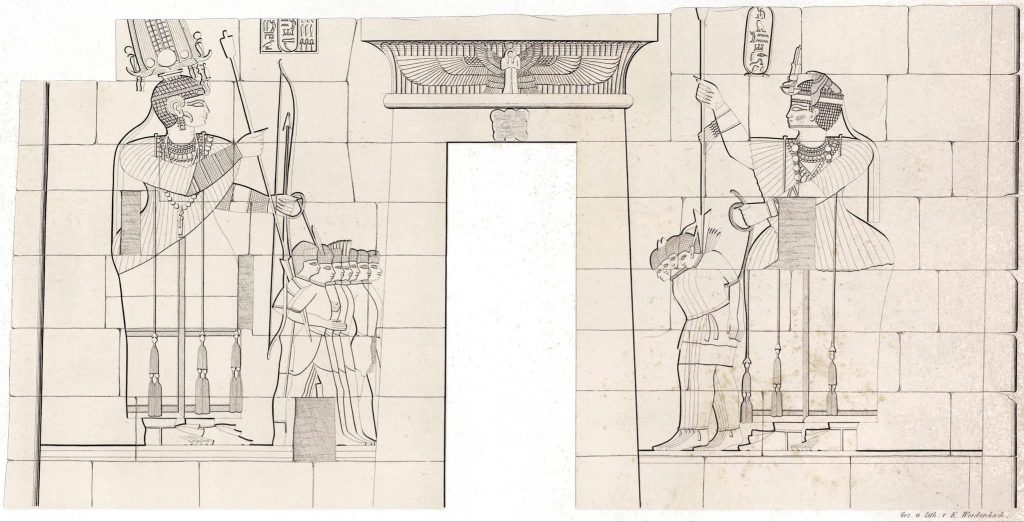

In the case of the School of Fine and Applied Arts, its faculty and student body were not spared harassment from previous regimes, which took the form of outright antagonism and in some cases expulsion from the college. The artist Abdul Rahman Abdullah, who goes by the name ‘Shanqal’, a Plastic Arts teacher at the Institute of Fine Arts and a member of the Sudanese Plastic Arts Union, touched on his educational experience, through which he meticulously familiarized sculpting students with Sudanese history. This can act as a foundation for the students to build contextually layered contemporary works of art, despite the gaps in Sudanese history documentation. Especially since the practice of sculpting was closely connected with the Meroic faith; however, it faded as an art form with the advent of Islam for their beliefs that didn’t serve any particular purpose to the Islamic faith itself.

Professor Abdul Rahman tells of their academic and personal efforts to keep the art of sculpture alive despite the open hostility towards it, displayed by ruling powers at the time to the sculpture practice; an attitude which didn’t necessarily reflect the opinions of the public at large. The professor recounts a particular recollection of a mural they once worked on drawing a positive reaction from the passersby. Curiosity prompted drivers to leave their cars to watch closely the installation of a giant Pasgianos mural near the Al-Azhari Roundabout in Omdurman. Judging by this incident, Professor Abdul Rahman was able to deduce that the public seems to have an inherent aspiration and eagerness for the arts, be it sculpting or other plastic arts, an eagerness that even the ruling powers and their censorship have not succeeded in quelling.

The stifling censorship that ruling regimes have been able to impose on individuals, institutions, and art colleges do not necessarily imply the state’s triumph in forcing its ideologies on the artist. Professor Abdul Rahman adds that these systems of oppression have only solidified the students’ political stance and sharpened their artistic production, fueling their resistance despite the underfunded learning environment and the opposing currents of thought.

Melting Ice and Nonconforming Art:

It’s safe to say that plastic arts are the most familiar discipline to the Sudanese public, and although plastic art paintings remain the more common forms of art in the local art scene, for many it is the aesthetic factor of the visual arts that takes priority in terms of its nature and its eligibility as a piece of artwork unto itself. Despite this, however, the history of Sudanese arts is rife with various distinct methods artists have devised and used as a means of expression, refusal, and mobilization.

An experiment conducted by the artist Mohammad Shaddad is a good example to analyze the interaction with and denunciation of the audience and art scene in general of unconventional works and concepts. The ‘Ice Exhibition’ is a name that will resonate with Sudanese art enthusiasts as one of the early forms of assemblage art in Sudan. Created by the artist Muhammad Hamid Shaddad in the mid-1970s, it consisted of a stacked construction of ice blocks surrounded by plastic bags that he had filled with colored water. It is a physical exploration of concepts from the Crystalist School such as transparency and dualism.3 This exhibition is considered to be one of the anti-establishment events held at that time, an antithesis of art exhibitions dedicated to diplomatic organizations the local art scene had catered to at the time.

The ‘Ice Exhibition’ is considered to be Mohammad Shaddad’s magnum opus; his crowning achievement in a series of conceptual movements he initiated during his time as a student at the College of Fine and Applied Arts. Through this movement, Mohammad Shaddad’s initiatives were connected by a consistent methodical pursuit of political and moral criticism. When he was still a first-year student at the College of Fine and Applied Arts in Khartoum, he set up his first solo exhibition titled ‘The Exhibition of the Seated Human being’; within the first hour of its set up students, professors, and various employees of the institute and even students from the Engineering and Commerce faculties crowded the hall and even stood at the windows to witness this remarkable event. Deep inside the college’s studio known as the ‘Tarikh’ (history) studio, a platform was set up with a chair on it, on which Shaddad had seated ‘James’, the painting department’s model at the time. James sat bare-chested, with a large piece of meat dangling a few centimeters above his head, and fresh loaves on display around him in the hall. Oil and watercolor paintings, and pencil drawings of Muhammad Shaddad were hung on the walls, and on the ground were three or four oil paintings Shaddad had borrowed from some fellow students, including a few from Dar al-Salaam Abd al-Rahim. Next to the paintings on the ground was a card with a statement written in clear handwriting: “The price of a painting is five kisses”. none of those gathered dared to pay the exorbitant price demanded for the performance; however, the focal point of provocation centered on Shaddad’s speech which he promptly launched into then and there, addressing the viewers directly. He claimed that ‘liberating instincts’ was a necessary step for human liberation; and that humanity’s salvation will only be achieved by casting off the legacy of repression inherited through the centuries by various ideologies, sacred texts, and superannuated customs made to alienate man from his very nature “as a being that seeks pleasure and flees from pain”.4

This event provoked the college community to such a degree that a group of students took it upon themselves to try Shaddad in a symbolic trial for his perceived transgressions, where he was condemned for his rebellious actions and sentenced to a symbolic punishment of ten lashes.5

Another example that revolutionized the meaning and vocabulary of Sudanese art is the Crystalist School Manifesto. Just as the Khartoum School was founded as a direct result of the absence of a plastic arts painting6, the Crystalist School was the spark igniting the flames of an idea that materialized in a particular painting. Made by the artist Kamala Ishaag, the painting was three and a half meters in length and depicted fifteen crystal balls of various colors, representing the relationship in life between man and plants. “Truth is relative, and absolute nature is dependent on man as a limited proposition. The struggle between man and nature always tries to find forms and claims for the opposite, that is, the absolute man, face-to-face with the limited forms and institutions in nature, which are themselves man-made. If the dialectic in classical modern thought is expressed with the phrases there are no isolated phenomena and man’s knowledge of matter lies in his knowledge of the forms of that matter’s movement, then we, in accordance with the idea of the crystal, may venture that the dialectic is a substitute for nature itself.” – The Crystalist Manifesto.7

The Crystalist Manifesto was published on the 21st of January 1976; with its philosophical and critical language, it managed to spark debates regarding the consideration of heritage in relation to art.8 In an attempt to distinguish itself from the path of the Khartoum School, as described by Dr. Salah Mohammad Hassan, who indicates that the bulk of the Crystalists’ interest in the work focuses on placing the concepts of ‘transformation’ and ‘becoming’ at the forefront of the plastic arts’ interest as a fundamental force, instead of the prominent theme of ‘Sudanism’ which focuses on the idea to ‘return to our roots’ unique to Khartoum School at the level of their style and aesthetic.

Moving on from 1976 to 2019 AD, peaceful protesters demanding justice at the Military headquarters in Khartoum lead to the largest exposition of art the Sudanese public had witnessed in decades. Many artists gathered their tools and headed to the Military Headquarters, making it their new art center. It was a ten square kilometer space packed with historical and cultural exhibits and various other works of art, and it helped shatter the barrier driving a wedge between artists and their audience, and between art theory and its practice. The space enabled the pursuance of the artistic process while bypassing conventional methods of presentation, thus representing a welcome and significant convergence where many kinds of expressive and conceptual arts can flow freely.

The gathering of assorted ethnic groups that make up Sudanese society at the Military Headquarters served to promote artistic diversity, manifesting itself in the diverse types of Fine, Performance, and Installation arts on display. Breaking the chains of restriction on expression was reflected in the surge of creativity, and the audience’s openness and acceptance of all the works presented.

The event led to a major spatial transformation in the Sudanese art scene, as well as to a modification of the Headquarters space into an art workshop comprised of the people’s various opinions and visions. With it came the revival of the Sudanese mural, sporting slogans, and political demands along with the artwork’s concept. A notable example is a mural demanding the prosecution of members of the previous regime, complete with a list of their names. Another example is a mural by the artist Alaa’ Satir, focusing on the women’s role in driving the revolution and the importance of their unity to keep the flame of resistance ablaze.

The permanence of the Art Space and its Cumulative Effects:

The desired goal is to channel the spirit and essence of the Military Headquarters sit-in space into art spaces inclusive of all facets of society and which commit to providing cultural and cognitive resources to the public. This was with the express aim of demolishing political and societal hurdles that exist between the individual and society at large, as well as combating elitist systems of producing and displaying art.

However, establishing an art museum or space comes with many challenges, not least of which is the marshaling of resources required for the existence of a comprehensive and inclusive cultural edifice. These can be material resources like construction and maintenance expenses and paying employees, or cognitive resources like theory application, analysis, and deconstruction of the nature and history of art and existing artwork, evaluating exhibitions and arranging public art programs with topics ranging from various themes of art and cultural history as well as the Sudanese visitor’s interests.

It is worth mentioning here that the history of art exhibitions in Sudan is rife with moments in independent spaces and commercial exhibitions and galleries that have embraced various works of art. Yet despite this, the absence of a permanent, tangible art space on the ground is a huge visual and cultural dilemma for the casual Sudanese viewer, who may hear of various artists winning awards for their practice, but will seldom have the opportunity to see the actual works themselves. For this reason, the virtual world has become a viable space for artistic presentation and research, with many contributing their individual efforts and sharing information and cultural resources. However, it is still of vital importance that there exists, a physical museum that houses the vast collection of artworks that contributed to the formation of the Sudanese art movement, with care taken to highlight the political, economic, and ethnic factors that affected the progress and trajectory of art in Sudan, as well as the artwork whose impact and influence is reflected on these factors as well.

It is also necessary to examine the experiences of neighboring African countries, since some of those spaces have experienced various factors that caused a rift between them and the public. A low turnout at art events remains prevalent, despite the museums’ attempts to entice the local populace with public programs and various art exhibitions. Their failure to attract a local audience indicates that the museum is viewed by the public as an elitist phenomenon9. This makes one question what process is used to select artists and officials, and the selection of artwork in a way that allows everyone to resonate and relate to them.

One of the more complex yet fundamental issues that are still debated is what defines (modern) art in a local Sudanese context, and who has the right to determine and define this framework. And how can this encompassing space cast off the spell of colonial museum history and the European imprint that has loomed over the concepts of exhibiting and curation.

Another facet of the collective artistic memory is the inclusion of the arts and its practice into various contexts to become an integral part of one’s daily life experience. Expanding the process of exploring and interacting with works of art beyond just the conventional exhibition space to include all public spaces, maybe the key to making art accessible to the public, which will in turn have a positive influence on the mental art space of the public’s collective memory. The ongoing collective contributions in a consistent manner are one of the most significant steps contributing to the development and enrichment of the contemporary cultural space since it is supportive of the interaction between artists and art enthusiasts and allows access to cognitive cultural means. The cumulative impact of these efforts will reflect positively on the conceptual and material aspects of Sudanese art.

The idea of establishing a permanent art museum may be slightly complicated on account of the colonial imprint it still echoes. However, the end goal is the stability of a permanent space, regardless of the name and shape it takes. The goal remains unchanged, which is to provide the public with access to all works of art with their varied contexts, mediums, and concepts, thus creating a portal to what the future will hold for art, and the worlds that shall emerge and thrive as a result of this necessary act.

References

1. The Party of Art: When the People Entered the Gallery. Hassan M. Musa. South Atlantic Quarterly, 109 (1): 75, 2010.

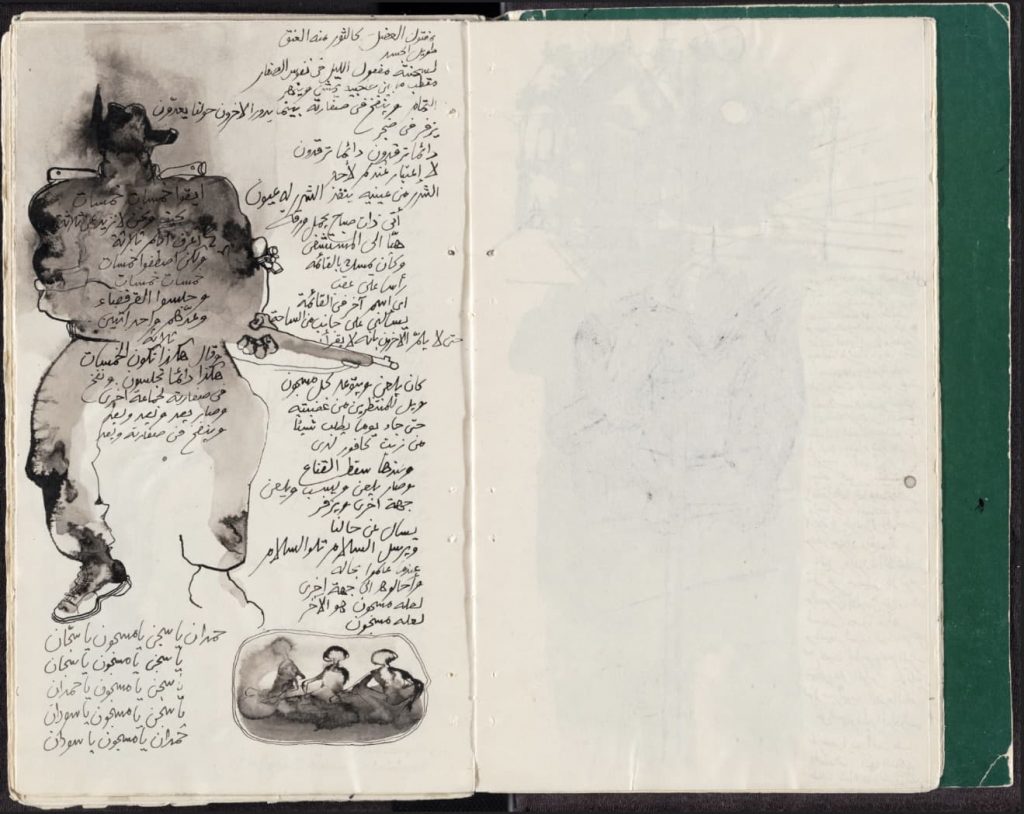

2. Ibrahim El-Salahi, ink on paper, Untitled from Prison Notebook, 1976, MoMA.

3. Prison Notebook. Ibrahim El-Salahi, 2018, Salah M. Hassan, P. 11.

ابراهيـم الصلحـي مـع طلبة وأساتذة كليـة الفنـون الجميلـة، الخرطـوم، أواسط الستينات. ملكيـة أرشـيف ابراهيـم الصلحـي، لندن .4

5. “We Painted the Crystal, We Thought About the Crystal”—The Crystalist Manifesto (Khartoum, 1976) in Context. Anneka Lenssen. 2018.

6. المرتكزات الفكرية والتشكيلية لمدرسة الخرطوم. اسماعيل حسن. ٢٠١٧

7. https://www.sudanmemory.org/cms/117/

8. Modern Art in the Arab World: Primary Documents – The Crystalist Manifesto

9. Contemporary Art and the Museum: A Global Perspective, 2007.

10. https://sudaneseonline.com/msg/board/18/msg/1398707985/rn/44.html

All artworks mentioned in the episode:

References used for the podcast:

1. The Party of Art: When the People Entered the Gallery. Hassan M. Musa. South Atlantic Quarterly, 109 (1): 75, 2010.

2. Prison Notebook. Ibrahim El-Salahi, 2018, Salah M. Hassan.

3. “We Painted the Crystal, We Thought About the Crystal”—The Crystalist Manifesto (Khartoum, 1976) in Context. Anneka Lenssen. 2018.

4. CONTEMPORARY AFRICAN ART from the SUr>AHE.SE. PERSPECTIV E, D R. RASHID DIAB. Del Documento, Los autores. Digitalizacion Realizada por ULPGC. Biblioteca Universitaria. 2006

5. ART AND THE AFRICAN WORLD: A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF THEIR INTERCONNECTION, KAREL ARNAUT, 1991

6. Modern Art in the Arab World: Primary Documents – The Crystalist Manifesto

7. Contemporary Art and the Museum: A Global Perspective,2007.

8. Ibrahim El-Salahi and the Making of African and Transnational Modernism by Salah M. Hassan

9. Back to Mangu Zambiri: Art, Politics, and Identity in Northern Sudan by Mohamed Abusabib

11. قبضة من تراب لإبراهيم الصلحي، كتاب صادر عن منتدى دال الثقافي في العام ٢٠١٢

12. المرتكزات الفكرية و التشكيلية لمدرسة الخرطوم. اسماعيل حسن. ٢٠١٧