Right to Public Space

The production team for this episode are:

Research and Producer: Almuzn Mohammedelhassan, Mai Abusalih, and Zainab Gaafar.

Presenter and Poster Design: Azza Mohamed.

Script: Almuzn Mohammedelhassan, Mai Abusalih, Zainab Gaafar, and Husam Hilali.

Music: Zain Records.

Audio Mixing: Tariq Suliman.

Project Manager: Zainab Gaafar.

Equipment and technical assistance: elMastabaTV.

Recording studio: 404 Creative Design Studio.

Original essay by: Wafa A. M. Ali

Translated By: Wafa A. M. Ali, Ahmed Amir Abd Alkhalig

Revision by: Mais Abdullah Saleh Abdulrahman

Public spaces are a means of recreation and relaxation in a crowded, sprawling city like Khartoum. Throughout the past thirty years, the government’s policies towards public spaces and their use can be summed up in approximately three keywords: privatization, restriction of use, and alteration of purpose. It is possible to say that Khartoum’s reserve of squares and public spaces has gradually eroded during the years of the Inqaz Regime. Every so often citizens wake up to find this park or that public square sold off or leased to a private investor. Soon after the walls rise around it and the gates close on it, and the public sphere gradually narrows.

In this article, we’ll take a look at some of the active public spaces that have emerged spontaneously without any kind of formal planning, and the fate of the ones that are formally planned. We will explore the role public spaces had to play in the country’s political history, After which, with the help of some examples, we will inspect how privatization policies contributed to the loss of public spaces, and the legal aspect of this systemic campaign to strip the city of its public spaces.

It can be argued that public space actually begins at the threshold of the house. The term “Mastaba”, referring to a slightly elevated paved surface in front of a house, is often the stage for many social activities; such as Ramadan’s Iftar or children’s outdoor activities. Oftentimes it is designed and built along with the house as a natural extension of it. However, we will be focusing, at a larger scale, on the public squares, plazas, and parks, starting with those that emerged with little to no urban planning

Among the most famous public spaces, especially in recent years, is “Atené” square. Its popularity persists despite its small size, peculiar origin, and the fact that it’s not technically a public space. Furthermore, its visitors and the nature of their activities have a special image in the collective imagination. Much of this recent popularity can arguably be attributed to “Mafroosh”, a monthly bazaar for second-hand books that was held in the square regularly from 2012 until it was discontinued in 2015.

Coincidence had a major role to play in the conception and subsequent development of Atené Square as a public space. However, the square itself is not public property per se, but is rather part of a private property owned by the Abu El-ela family and was built during the Independence era (mid-1950s). Designed by N. Stephanis, the real estate includes five office buildings and is located at the intersection of Al-Qasr and Al-Gomhouria streets, one of the busiest intersections in the city, making it easily accessible from most of downtown Khartoum. Out of the five planned buildings, four were fully constructed while the plot in the center, which should have been the fifth building, remained empty except for a few short columns and the entrance and exit of the car parking in the basement. This space later became Atené Square. This central positioning made the square “immersed” between the other buildings, sheltering it from the noise of the nearby streets. The surrounding buildings cast their shade on the square since late afternoon, making it a suitable venue during the daytime, unlike other public squares or plazas that are exposed to direct radiation for most of the day. On top of all that, the square is surrounded -on three sides- by small shops and stores overlooking verandahs, making it active all day long, without getting too crowded.

Perhaps Atené’s property nature as private was its greatest advantage; it minimized the government – or governments’ -ability to expropriate it or restrict its use. This is a strange paradox. That it is Atené’s dependency on the private sector that protects its public use from government requisition! This paradox becomes evident given the story of “Mafroosh” Bazaar.

Mafroosh’s first event was held in May 2012, led by an initiative from Work Cultural Group, in the square chosen specifically for its symbolism, as it has been a meeting place of intellectuals for decades. The bazaar is based on a simple idea; On the first Tuesday of every month, about twenty to fifty booksellers display on the ground their merchandise of old, second-hand, new, rare, or forbidden books -hence the name Mfroosh that means to be laid on the ground in Arabic.2 Transactions were carried out by either sale or books exchange. The bazaar attracted hundreds of visitors Of different ages and demographics, as it was a place to meet with friends and interact with others over a period of time that extended from early afternoon until nine in the evening. Sales were not limited to books, as handicrafts were also displayed, and it was accompanied by a musical performance every once in a while.

The bazaar was not sponsored by any government institution which did not pose any problem for the first two years. However, interference started soon after the restrictions that followed the crackdown of September 2013 protests. Organizers were hindered from holding the bazaar by trapping them in a series of bureaucratic procedures, under the pretext that they had to submit a list of every single book title to be displayed if they were to proceed with the event.3 A feat that is impossible for a bazaar centered around its visitors’ free exchange of their used books. After a hiatus lasting several years, Mafroosh was eventually brought back to the “Qiyadah” sit-in, after which it was held regularly in the National Museum.4

Mafroosh created a space for culture at a time when the restrictions imposed on it by the authorities were tightening, and the venues for public activities were shrinking. When the government was unable to get rid of the square by selling it off or barring public access to it, as is usually the case with “Actual” public squares, they proceeded to obstruct Mafroosh through the black hole of bureaucracy. It does not seem that the problem was with Mafroosh or Atené, insomuch as it was in the free space they provided. A space that dictatorial authority views as cancer that must be eradicated.

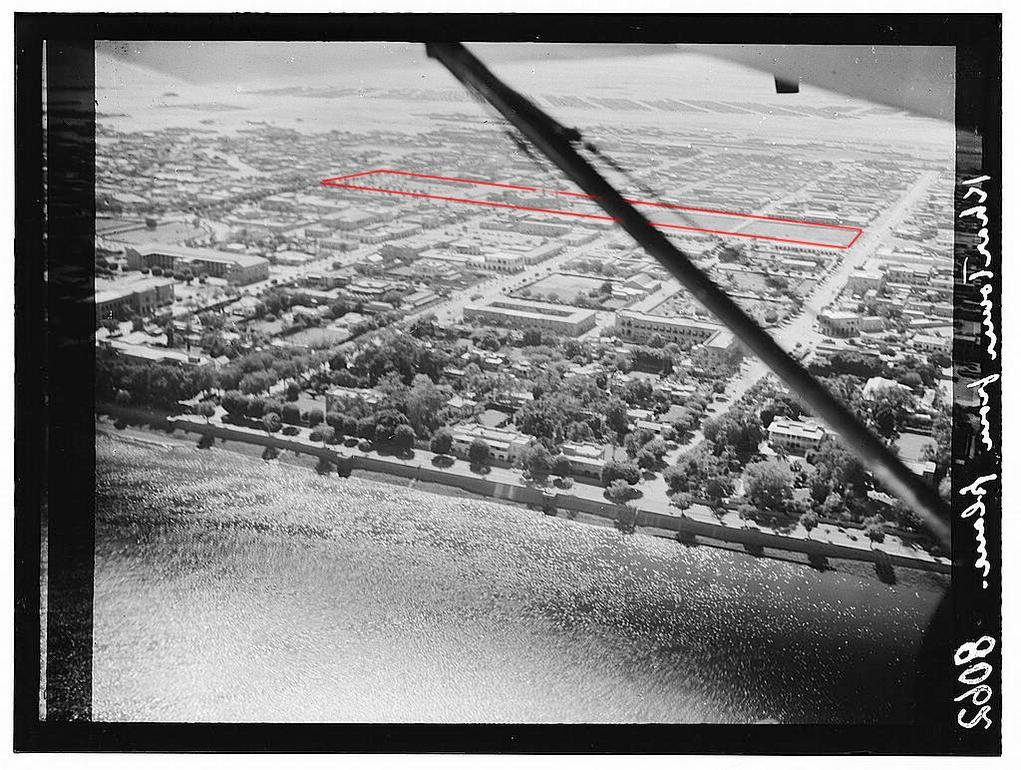

Another area in Khartoum that can be considered a product of happenstance is Khartoum’s Nile Street, which gradually became an important outlet for the city, fostering hundreds of small businesses relying on its existence as a public space frequented by all city’s inhabitants.

The privatization of the riverfront by opening it up to investment can be observed in the eastern-most segment of Nile Street. Between the Armed forces and Mansheya bridges, several privately owned facilities can be observed, such as Alnadi Alwatani (National club) or wedding venues. This pattern of encroachment on public space, which is only beginning in this part of Nile Street, is officially institutionalized in Khartoum’s Structural Plan (the latest urban plan for Greater Khartoum), specifically in the plan for the Muqran area and Al-Sunut forest. There is a clear orientation to transform the area into a concrete forest of some kind. The plan will densify the area and turn it into a business district, stacked with office towers.6 Most of the area between the Blue Nile and Nile Street will be privately owned, meaning that access to the riverfront will become a privilege and not a right in a city permeated by three rivers. A tender to implement the 25 years-long plan was opened to both local and international companies alike in 2005.7 It does not seem that a project such as Al-Muqran takes into consideration the fate of the aforementioned users of the space, be it the small businesses owners or their customers or regular visitors, not even the urban fabric of the city.

It is important to mention Mafroosh and Nile street in this context since they are arguably considered central public spaces, and because they were not planned but rather came into existence as a result of people’s needs and the way they utilized these spaces. For a brief while, however, the sit-in area in front of the General Armed Forces Command was the central “square” of the city. In one way or another, it showcased all the activities you would expect to find in a typical public square; a spontaneous meeting place for friends after work hours, a venue where big events and concerts are occasionally held, or a place where people would meet just for chatting and exchanging ideas and views. The sit-in area was spontaneously utilized for all these uses while people were occupying it, but the purpose that was intended the moment the crowds reached it, was to make their voice heard. It was a political intention that led them there.

This political intentionality is an important characteristic of the utilization of public space in Khartoum. The memory of the city with revolutions and civil movements is an old one. A memory that stretches back to even before independence. It is impossible to write about public space in a city like Khartoum, without bringing up those moments, when thousands of footsteps were engraved as a vivid memory still imprinted on the sidewalks, the dirt, and the asphalt of streets.

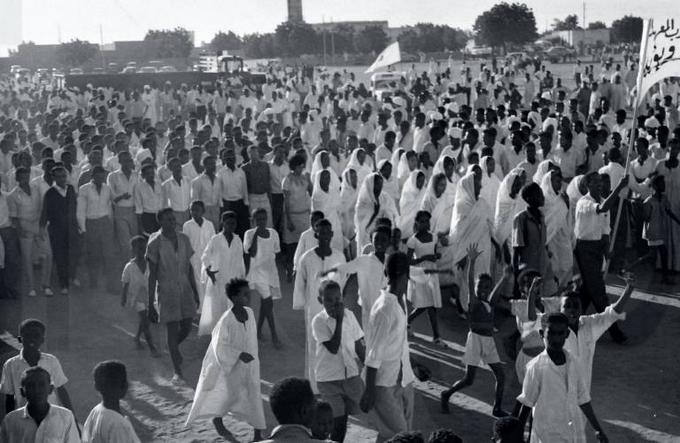

Abdel Moneim Square –which later came to be known as Nadi Alusra or The Family Club– was the first stage of the October 1964 Revolution, where the funeral prayer for the martyr al-Qurashi took place. The second stage being Al-Gamma Avenue, where, on the twenty-eighth of October, thousands of citizens headed towards the Republican Palace, crowding the surrounding streets.10 The angry footsteps of protesters resonated on Al-Qasr Avenue during the April 1985 Revolution. They spilled out into the street from Khartoum’s main railway station all the way to the Palace.11 As for the “Qiada” (Army Headquarters) itself – the Center stage of the December 2018 revolution – it is not a square but a group of streets surrounding the General Armed forces Command, and as a gathering point for a number of main streets, it is one of the city’s central areas.

Suffice it to say that with the exception of Abdel Moneim Square, most of the civil movements took place in streets, and not the public squares. Why, then, were most major political events associated with the streets? Why Al-Gamma and Al Qasr Avenues, and not Abu Ginzeer Square, for example? After all, squares such as Al-Tahrir in Cairo or Tiananmen in Beijing were center stages for important political events. Is it because Khartoum is already short on public squares? Or because the existing squares have their own problems? What prevented these squares from being the stage of such events?

A brief historical overview of Khartoum’s central public squares, such as the former Abbas, The United Nations, and Abdel Moneim Squares, as well as the remaining ones like Abu Ginzeer Square, can give us an insight into the reasons behind this. The story of the United Nations, and Abdel Moneim squares, in particular, can shed a light on the policies of privatization and repurposing institutionalized by former governments. The greatest manifestation of the state’s hostile policies towards the existence of a freely accessible and active public venue, is the fact that Abdel Moneim Square was once a hub for rallies and civil movements in the 1950s and 60s, but this role gradually diminished until it completely disappeared from the collective imagination.

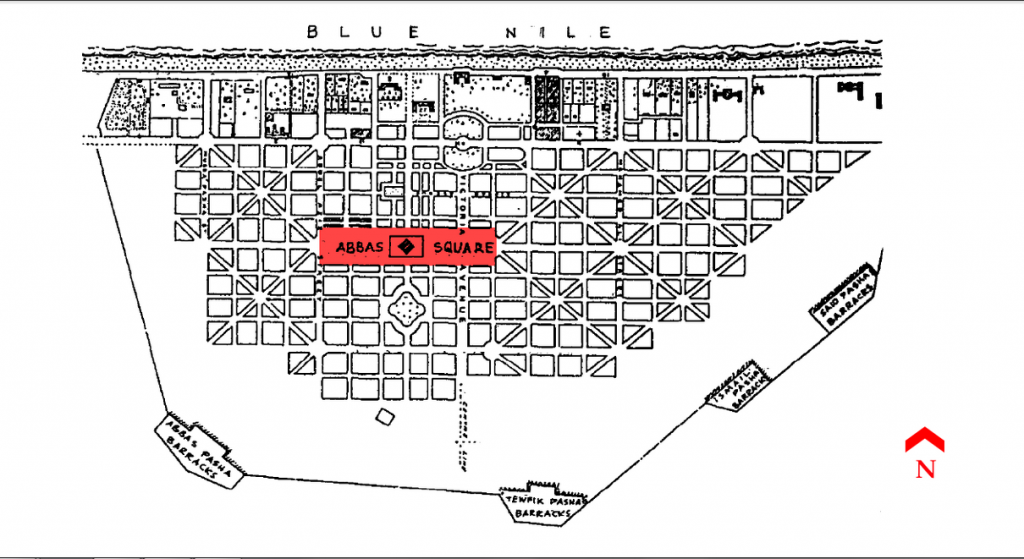

Let’s start first with Khartoum city’s first formally-planned square; Abbas Square (named after Khedive Abbas). It was the central square of Kitchener’s Khartoum, and it continued to serve as the main square of the steadily expanding city, with the Grand Mosque in its center -as typical in many Arab cities- surrounded by the main market. The square was split by Victoria Avenue, the widest in Khartoum back then.14 With the continuous expansion of the city, however, the square gradually shrank as the buildings crawled and swallowed it, until all that was left of the original square were two small squares: The United Nations and Abu Ginzeer Squares.

Abu Ginzeer Square is named after the owner of a grave surrounded by iron chains (Ginazeer) that was located at the center of the square. In recent years it was cordoned off by a fence, and during the recent December 2018 revolution security forces were stationed there. As if paramilitary forces occupying a public square -as the most blatant manifestation of state militarization- was not bad enough, the square was converted, during the December revolution, into a gathering point for protesters arrested during marches in Khartoum’s downtown, from which they are sent to various detention centers.16 17

The United Nations Square had multiple uses; the southern part of it was a football field, and the northern part had a vegetable market called al-Zinc Market. It withstood the changes until Nimeiri’s era after which it became Al-Quba Alkhadra (Green Dome) Library, which was later demolished and the Waha (Oasis) Towers were built on its site. 18 As for the reason behind the square’s name, it was where the United Nations flags were once raised.

Abdel Moneim Square is the main square of the Khartoum 3 neighborhood. Its plan contrasted significantly with Kitchener’s original Khartoum plan. In contrast to the uninterrupted iron grid, Khartoum 3 was laid out around a circular center represented by Abdel Moneim Square. As previously mentioned, in the fifties and sixties, the square was the stage for important events in the city’s memory. Events that exerted considerable influence on the rest of the country, as seen in the Al-Gezira farmers’ sit-in in the square. On the 29th of December 1953, twenty five thousand farmers from Al-Gezira region along with their families, occupied the Square and succeeded in forcing the government to recognize their union.19 Another significant event took place on the 17th of November 1958, when the representatives of Parliament met to vote on a “withdrawal of confidence” from Abdullah Bey Khalil’s government, who tried to impede their efforts by postponing the parliament session and handing over power to the army the next day.20 The aforementioned funeral procession of al-Qurashi, which marked the beginning of the end for Abboud’s regime, also took place in the square. Colleagues and professors of al-Qurashi -a student at the University of Khartoum at the time – along with the citizens, who joined them, marched carrying his body, all the way from Khartoum Hospital, along the Isbitalia Street and across Hurriya Bridge towards Khartoum 3 neighborhood, where they held his funeral prayers in the square. His body was then sent back to be buried at his hometown, Al-Qurassa village in Gezira state. 21

The square was later converted to Nadi Al-Usra (The Family Club.) Its considerable size allowed it to host various sports, social, and political activities. It included arenas and halls for various sports, including tennis, squash, and billiards. It also hosted many political seminars. Most importantly, it was a recreational destination for the families who lived in the neighborhood and nearby areas up until the early nineties. From then on, the authorities began to restrict its use, then began to gradually cut off pieces of land and reassign them to various other purposes; sometimes as headquarters for government institutions or security services, other times to be sold off to private investment.23 The fierce raid of privatization on the club makes more sense when considering the value of the land; the plot of land on which the club was built is among the most expensive in Khartoum.

What makes Abdel Moneim Square significant is that it can be viewed as a historical record for understanding the relationship between public space and the state. It was originally designed to serve the neighborhood’s level, and perhaps the nearby neighborhoods, not the city level. However, as evident from the history of the square, at some point it served a greater level than the city itself. The square also reveals the wasted potential of neighborhoods’ squares, as demonstrated by the period it was developed to house Nadi Al-usra. On top of it all, the square is an example of the hostility with which the state deals with public spaces, especially during the thirty years of the Inqaz era. This hostility created a clear pattern, evident in a systematic campaign to take over public squares, starting from the large city squares, to even neighborhood’s squares. The audacity of this takeover campaign reaches the limits of insolence in small squares scattered across neighborhoods, and far from the monitoring eyes of the public.

So how did neighborhoods’ squares fall prey to the greed of governments and private investors? To understand this we must answer a few questions: How was this expropriation trend initiated? And how did the urban planning of the city in general and the urban design of these very squares facilitate the continuation of this trend?

According to Dr. Osman Al-Khair, an architect and researcher specializing in the field of human settlements, It can be argued that the first seeds of this pattern were sown in Abboud’s regime, the first military dictatorship. During Abboud’s era, residential districts were planned with vastly spacious squares, e.g. Al-Thawrats in Omdurman. Later, during Nimeiri’s regime and its successive financial crises, the government turned its gaze toward these vast squares, with their land values increasing as they were now located in the center of the expanding city. Nimeiri’s administration began to slice off longitudinal strips of land from the squares’ perimeters and divide them into residential plots to be auctioned off. Since these squares were larger than the neighbourhoods’ needs, this step in and of itself was not problematic, as it was an attempt to control the urban sprawl of the city that was spiraling out of control. The problem is that this policy has opened the door wide for the expropriation of these squares.24

One of the most prominent factors facilitating this encroachment of neighborhoods’ squares, by making it difficult to notice and thus to take action against, is the fact that most of these squares are virtually deserted. The empty plots of land are devoid of life and rarely ever utilized, and if so, then mostly as a landfill or a shortcut. According to Dr. Othman Al-Khair, The abandonment and the subsequent desertion of these squares was likely a result of service facilities and commercial activities concentrating on the perimeter of the neighborhoods, to be closer to the asphalted main street. This resulted in the death of the neighborhoods’ inner center, which is usually where the square is situated. This desertion alienates it from the memory of the neighborhood’s residents, and thus further distances it from the eyes of public monitoring.25

Of course, this reasoning alone is not enough to completely account for the shrinking of these squares. However, when adding to all of the above an elastic planning law, with no clear checks and balances for the officials entrusted to implement it, and without regulations explaining it, the equation becomes complete to strip the neighborhoods of squares and the city itself of public spaces.

Perhaps shedding a light on some of the legal aspects concerning the planning and use of public space, can offer a glimpse into the previous regime’s perspective on public spaces. It can also further explain the reasons behind the vague and elastic bureaucratic procedures that hinder the protection of these spaces, thereby facilitating their grapping and privatization .

According to Salwa Abasam, A lawyer and an activist in civil society organizations, The current law regulating the planning and use of land is The 1994 Urban Planning and Land Disposal Act, that replaced The 1406 AH Land Disposal Act, The 1406 AH Urban Planning Act and The 1950 Town Replanning Act.26 The 1994 Act is brief, with only 49 articles, therefore, it needs a lot of explanatory and complementary regulations, and this is exactly where the problems with this law begin. But before we delve into these problems, we must have an understanding of the officials and institutions involved in implementing this law. First, there is The Federal Urban Planning and Land Disposal Council, which is the body primarily responsible for setting general policies and plans and overseeing their implementation. Then for each state, there is the Minister of Urban Planning and The State Planning Committee.27

Within the jurisdiction of the Supreme Council for Urban Planning, detailed in Article 8 of the 1994 Act, is to “Approve the change of field of land use…with the exception of public spaces and squares.”28 The jurisdiction to change the land use of public spaces was granted to the minister and the planning committee in their respective states, in accordance with Article 9, which defines the authorities of the minister, on whom also falls the task of approving directed maps. These maps detail the required services for the area as well as land use, including public spaces and squares. Article 9 grants the minister the authority to “recommend the change of use of public spaces and squares, for any purpose, where necessity requires the same.“29 and assigns the task of approving or rejecting this recommendation to the state planning committee; i.e. , it is the committee that determines what is a “necessity” that requires change. The odd contradiction is that the decisions of this committee are appealed by the minister himself. According to Article 42, The Minister also has the authority to “…dispose of the planned land the purposes of which have been specified, by way of preferential allotment…”30 The article regulates this allocation which goes through the same aforementioned procedure, of being approved or rejected by the state’s planning committee.

Now back to the problematic part of the law. Salwa Abasam explains that expressions such as “where necessity requires the same.” are loose, flexible, and can be interpreted at the whims of the executive authorities. The ideal situation is that any ambiguities of this nature should be detailed and clarified in the technical and executive regulations of the law. In reality, what was actually happening is that throughout the past thirty years, there was a tendency or propensity to issue regulations that are inconsistent with the laws under which they were issued. Many of these regulations could not even be viewed as they were never officially published. For any regulation to become valid and acquire the legitimacy of a valid law, it must be technically sound and contradict neither the law it was issued under nor the constitution. Most importantly, it must be published in the Official Ministry of Justice’s Gazette, which is not the case with the regulations interpreting the 1994 Urban Planning and Land Disposal act.31

The lack of transparency and the ambiguity of this law, and consequently the bureaucratic procedures, makes the task of monitoring the executive authority and safeguarding public interests next to impossible. How can people be expected to know that repurposing this square, or selling off this public space Was in violation of a law they weren’t aware of existing in the first place? This policy of keeping the general public in the dark is not a new concept to the Inqaz regime, rather it is the very tactic which enabled it to stay in power for thirty years, and this blackout is not limited to the land administration but extends to the entire body of the executive authority.

Governments’ policies towards public spaces reflect their appreciation of the public sphere in general, whether real or virtual, as a free venue to exchange opinions in an open society that interacts among itself. Public spaces are an integral part of this interaction process and an important stage for it to take place. Dictatorships always tend to restrict this interaction, driven by a survival instinct to fiercely defend their existence against the consequences of this free interaction. consequences that start with protesting a certain program or policy, to even protesting the existence of the dictatorship itself. On the other hand, and as the Washington Post’s slogan suggests, “democracy dies in darkness.” A healthy democracy can only be born in a sphere that is open and accessible to everyone in the society with no exceptions, and it cannot be sustained in the absence of public spaces that embrace people from all walks of life.

1 @SudaneseCulture. “Eteni Square, Khartoum, 1970’s, Sudan. . . .” Twitter, 29 Mar. 2018, 9:29 p.m., https://twitter.com/SudaneseCulture/status/979440538712764416?s=20.

2 بشير، يوسف. “(مفروش) معرض للكتاب على الهواء الطلق !!” المجهر السياسي، 15 أبريل 2014، https://www.sudaress.com/almeghar/19422. تم الوصول إليه 30 مايو 2021.

3 هلالي، حسام. “الثقافة في السودان.. حكم البيروقراطية والمناورات.”ألترا سودان، 30 أغسطس 2015، https://ultrasudan.ultrasawt.com/ . تم الوصول إليه 3 يونيو 2021..

4 “عودة ﻣﻌﺮﺽ ﻣﻔﺮﻭﺵ ﻟﻠﻜﺘﺎﺏ ﺍﻟﻤُﺴﺘﻌﻤﻞ ﺑﻤُﺘﺤﻒ ﺍﻟﺴﻮﺩﺍﻥ ﺍﻟﻘﻮﻣﻲ.” صحيفة التحرير، 2 أكتوبر 2019، https://www.alttahrer.com/archives/36614 . تم الوصول إليه 7 يونيو 2021.

5 Work Cultural Group. Mfroosh in Sudan National Museum. Facebook, 1 Oct. 2019, 7:57 a.m., https://web.facebook.com/WorkCulturalGroup/posts/2641406809249081?__tn__=-R. Accessed 21 June 2021.

6 Osman, Amira. “Sudan student protests show how much city planning and design matter.” The Conversation Africa, 5 May 2016, https://theconversation.com/sudan-student-protests-show-how-much-city-planning-and-design-matter-58877. Accessed 30 May 2021.

7 Ibid.

8Matson Photo Service, photographer. Sudan. Khartoum. Banks of the Blue Nile looking up stream. 1936, Photograph, Library of Congress, Washington D.C., www.loc.gov/item/2019708079/. Accessed 21 June 2021.

9Matson Photo Service, photographer. Sudan. Khartoum. Banks of the Blue Nile looking down stream. 1936, Photograph, Library of Congress, Washington D.C., www.loc.gov/item/2019708078/. Accessed 21 June 2021.

10“تحت المجهر – ضد حكم العسكر – ضد عبود.” يوتيوب، رُفع بواسطة قناة الجزيرة، 4 أكتوبر 2013، https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ij5OZnKTeWU&list=WL&index=18&t=2324s. تم الوصول إليه 3 يونيو 2021.

11 “يوميات أبريل.. أجواء مشحونة.” الصحافة، 7 أبريل 2012، سُودَارِسْ، https://www.sudaress.com/alsahafa/43984. تم الوصول إليه 30 مايو 2021.

12 “In New Protests, Echoes of an Uprising That Shook Sudan.“ The New York Times, 23 Feb. 2012, https://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/24/world/africa/echoes-of-an-arab-revolution-that-rocked-sudan-circa-1964.html. Accessed 21 June 2021.

13 “The neighbourhoods of Khartoum: Reflections on their functions, forms and future.” Habitat International, vol. 16, no. 4, 1992, pp. 27-45.

14 Ahmad, Adil Mustafa. “khartoum blues: the `deplanning’ and decline of a capital city.” Habitat International, vol. 24, no. 3, 2000, pp. 309-325.

15 Matson Photo Service, photographer. Sudan. Khartoum. River in foreground. 1936, Photograph, Library of Congress, Washington D.C., www.loc.gov/item/2019691482/. Accessed 21 June 2021.

16 “تغطية مستمرة..خروج موكب “ضحايا الحروب والانتهاكات”: خيام للاعتقال “بأبي جنزير”” التغيير، 14 فبراير 2019، https://www.altaghyeer.info/ar/2019/02/14// تم الوصول إليه 5 يونيو 2021.

17 بشير، حسن. “عاجل بالصوره : معتقلين الخرطوم الأن في ميدان ابوجنزير” السودان نيوز 365، 17 يناير 2019، https://www.sudannews365.org/4075/ تم الوصول إليه 5 يونيو 2021.

18 الزاكي، عائشة. “معالم الخرطوم زمان.. أيام زمان أيام السرور” الإنتباهة، 28 مارس 2014، موقع النيلين https://www.alnilin.com/906821.htm تم الوصول إليه 30 مايو 2021.

19 “في ذكرى المعارك الكبرى مزارعو مشروع الجزيرة وموكبهم في 29 ديسمبر 1953.”التغيير، 26 ديسمبر 2015، https://www.altaghyeer.info/ar/2015/12/26 تم الوصول إليه 30 مايو 2021.

20 حاج حمد، محمد أبو القاسم. السودان: المأزق التاريخي وآفاق المستقبل 1956-1996.الطبعة الثانية، المجلد الثاني، فينبار ف. ديمبسي وشركاه، 1996. ص 207

21 أسباب وتأثيرات أحداث أكتوبر 1964م على الحياة السياسية حتى عام 1969م (The Causes and Effects of October 1964 Events on The Political Life Until 1969). Abdel Karim, Ahmed Babiker Mohamed Khair 2011. University of Khartoum, PhD thesis. University of Khartoum Dspace, http://khartoumspace.uofk.edu/handle/123456789/12094

22 “ABDEL MONEIM SQUARE ANNIVERSARY OCTOBER REVOLUTION IN KHARTOUM, SUDAN 25 NOVEMBER 1964” IMAGO, https://www.imago-images.com/st/0081524090. Accessed 15 June 2021.

23 الخليفة، ناذر محمد. “نـادي الأسـرة بالـخـرطـوم (3 ) !!!”سودانيز أونلاين، 4 أكتوبر 2006، https://sudaneseonline.com/board/110/msg/1189281033.html تم الوصول إليه 30 مايو 2021.

24 Al-Khair, Osman. Interview. By Zainab Gaafar. 11 Sep. 2020.

25 Ibid.

26 Abasam, Salwa. Interview. By Zainab Gaafar. 12 Sep. 2020.

27 السادس.وزارة العدل- جمهورية السودان. https://moj.gov.sd/sudanlaws/#/reader/chapter/138. تم الوصول إليه 26 مايو 2021

28 Ibid.

29 Ibid.

30 Ibid.

31 Abasam, Salwa. Interview. By Zainab Gaafar. 12 Sep. 2020.

Extra References used for the podcast:

- Awad, Zuhal Eltayeb. “Evaluating Neighborhoods Developed Open Spaces In Khartoum-Sudan”. Civil Engineering And Architecture, vol 6, no. 6, 2018, pp. 269-282. Horizon Research Publishing Co., Ltd., doi:10.13189/cea.2018.060601.

- Bahreldin, Ibrahim Zakaria. “Beyond The Riverside: An Alternative Sustainable Vision For Khartoum Riverfront Development”. Civil Engineering And Architecture, vol 8, no. 2, 2020, pp. 113-126. Horizon Research Publishing Co., Ltd., doi:10.13189/cea.2020.080209.

- Bashari, Wala et al. “Spatial Impact Of Gender Variation On Khartoum City River Side Public Open Space”. Sudanese Institute Of Architects, 4Th Scientific Conference, 2015. Researchgate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/307883060_Spatial_impact_of_gender_variation_on_Khartoum_city_river_side_public_open_space. Accessed 5 June 2021.

- Gali, Naser. “Urban Design Of Open Common Spaces In Khartoum State”. Sudan University For Science & Technology, 2017.

- Layton, M. City Of Khartoum, including Khartoum North and Omdurman cities Drawn In 1952, Map.The Sudan Survey Department, 1952, Khartoum, The David Rumsey Historical Map Collection online archive, https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~318985~90087926:Alkhartoum. Accessed 7 Jun. 2020.

- Mohammed, Mohammed Badawi. “دراسة حول قوانين النظام العام السودانية”. Tamas, http://badawitamas.blogspot.com/p/blog-page_58.html. Accessed 5 June 2021.

- الطيب, عبد الله محمد. الرسم على الهامش. دار سيبويه للنشر، بيرمنغهام، بريطانيا، 2014.